Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Twenty-Two

By Brad Westwood

Many of the west side’s earliest immigrants found employment in mining, transportation and smelter industries. Others bought and sold goods essential to frontier life. This segment speaks to the Cornish, Irish and Jewish American Communities who lived and worshiped on the west side.

Many immigrants left their homelands because of famine or the mechanization of agriculture. Others fled because of political unrest or religious persecution. In all, Salt Lake City and its west side became home to a diverse population of peoples who joined Utah’s Native American peoples, Mormon immigrants, and peoples who emigrated from western Europe earlier during the nineteenth century.

Many of Utah’s earliest settlers moved from Western European countries including Wales, Ireland, and England. Irish immigrants arrived in America en masse during the devastating potato famine that spanned from 1845 until roughly 1853. Many Irish Americans worked alongside Chinese immigrants to construct the transcontinental railroad which came to its completion in Utah. Irish immigrants settled into life in Utah by making their mark on the social, religious, and political culture of the territory. For example, during the Civil War, Irish American Colonel P. Edward Conner, commanded Camp Douglas (later named Fort Douglas) located in the foothills east of Salt Lake City. Conner and his soldiers, or volunteers, from California and Nevada, prospected across the Wasatch and Oquirrh Mountains to launch commercial mining in the Utah Territory. In the following decades, census records indicate that English, Scandinavian, Irish, and Italian workers found employment in Utah’s early mines.

Some of Utah’s nineteenth century immigrants sought an escape from religious persecution. Many Jewish people began to arrive in Utah during the California Gold Rush. Thereafter Jewish American merchants purchased wanted goods in the Midwest or in California, then freighted these goods to Salt Lake City retailers, or they set up temporary tents for trading and selling. Some of these freighters eventually started brick and mortar businesses in Utah. Their shops and services provided much-needed supplies to Salt Lakers, and to many overland travelers who stopped in the city to replenish supplies. The city’s Jewish businesses sold dry goods, fabric and fancy goods, farming and mining equipment. Utah’s Jewish American story is one of earliest migrant or immigrant experiences. Besides the story of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its wave of East United States migrants, and European and Scandinavian immigrants, Utah’s Jewish communities were one of oldest religious groups to settle in Utah.

“Utah’s Jewish American story is one of Utah’s earliest and most successful minority experiences.“

Most of Salt Lake City’s Jewish merchants opened stores near Temple Square and later between 300 and 500 South on Main Street (originally East Temple). Jewish shops and large commercial retail stores established an enduring presence that lasted well into the mid-twentieth century. Business blocks extending outward from 300 to 400 South Main Street eventually became known as the non-Mormon or gentile business district. Utah’s early Jewish residents and their synagogue started in the Pioneer Park neighborhood.

In 1866, using the symbolic name “Independence Hall,” a group of religionists beyond Mormonism – led by a Congregational Church minister Reverend Norman McLeod, from the American Home Missionary Society – built at 300 South and Main Street (East Temple), a small public meeting hall. The real estate and the construction for this hall was paid by subscription from various Christian missionary sources from California to the East Coast. On the local Independence Hall board were a number of Jewish businessmen, who used the hall to hold literary society meetings, offered to any and all who wished to participate. This may be considered the first public gathering of Jewish peoples in Salt Lake City.

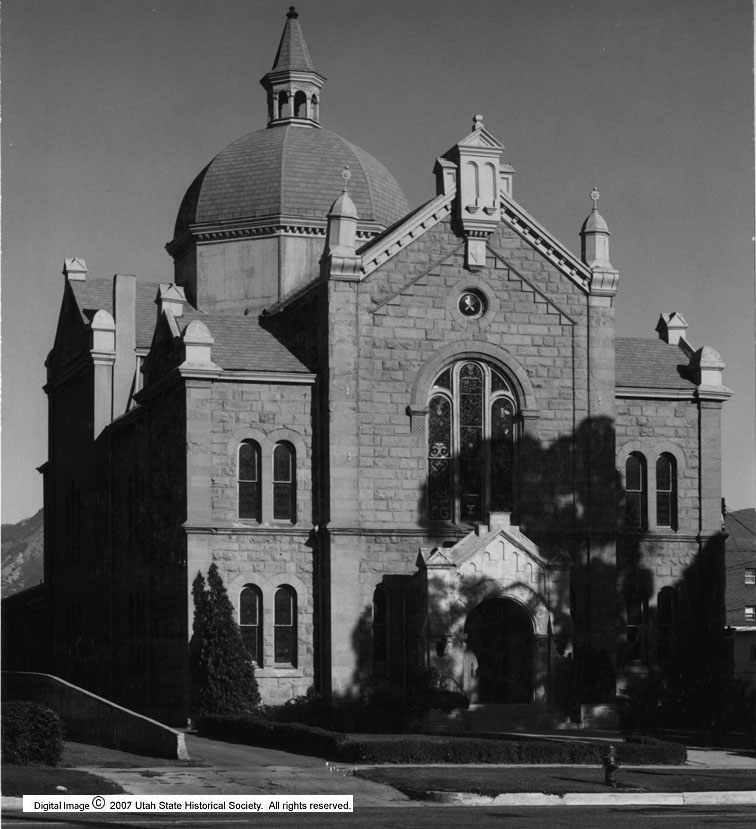

In 1881, Salt Lake City’s Jewish community built its first combined Beth midrash (study hall) and synagogue, known as Congregation B’nai, on the west side on the corner of 200 West and 300 South. The group eventually moved eastward to a larger temple. There were three different Jewish congregations in Salt Lake City including the B’nai, the Montefiore, and the Sharey Tzedek that opened its doors in 1916. From World War I to the 1980s, many Jewish residents opened and ran both small and large businesses in downtown Salt Lake City, including Gallenson Jewelry, Guns & Pawn, Max’s Clothing, Tannenbaum’s Army & Navy, Wolfe’s Sporting Goods, Axelrod Furniture, and Zink’s Sporting Goods. Others expanded into dozens of businesses and professional fields. Salt Lake City’s growing Jewish community remains an active part of twenty-first century Salt Lake City.

Members of Salt Lake City’s early Jewish American communities have left behind records that provide a glimpse into Jewish life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Utah. Izzi (Irvine) Jerome Wagner led a full and interesting life based early from his west side home. His biographer, Don Gale, explains that Izzi grew up on 300 South, which was a busy urban street. Wagner’s father, Harry (whose surname was formally Wigrizer), had immigrated from Ukraine while his mother, Rose Yuddin came from Latvia. The Wagner’s lived in a small pioneer adobe house, with an outhouse in the backyard, and the family’s water sources coming from a pump in the front yard. The home was located at 144 West and 300 South where the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center now stands. Wagner’s parents represented different parts of Eastern Europe but shared in a desire to establish a new home in the American West.

Harry Wagner, like many Jewish Americans, worked in several jobs during his lifetime. Harry started out in the transportation business, moving passengers, luggage, and freight from west side train depots to the city’s hotels and boarding houses. First with a horse and wagon, later with a used motor truck, Wagner often picked up miners – many Italian, Greek, or east Europeans – coming from points west and south for the weekend, seeking a good time and a chance to buy provisions. He often took his customers to small hotels on 200 and 300 South streets. From time to time, the senior Wagner paid the neighborhood’s young men to lift and transport his heavier freight. One such strongman was Jack Dempsey, who reigned as the heavyweight champion of the world from 1919 to 1926. Dempsey, born in Manassa, Colorado set up bar room fighting matches in Salt Lake City’s many taverns to hone his pugilistic skills.

Three of Izzi’s childhood stories offer insight into life on the west side. Every week, Izzi’s mother would visit a boarding house in Japan Town, just two blocks to the north, and paid 25 cents for a tub of hot water to bathe herself and her children. While waiting at the top of the boarding house stairs, for his turn in the copper tub, Izzi would listen to Japanese patrons speaking candidly to one another below. Over time, the boarding house owner’s son became one of Izzi’s lifelong friends. His relationship with this young man demonstrates how people from different backgrounds forged enduring relationships in the diverse west side.

Immigrants from other nations often blended their cultural traditions with local customs. For instance, the Wagner’s spoke Yiddish and Hebrew at home, and Izzi and his siblings spoke English at school. Harry and Rose also spoke Russian and would use the language when they talked about a topic that they did not want their children to understand. During his childhood, Izzi delivered food and other orders from the Rexall Drug Store to prostitutes living near his 300 South home. One hotel that Izzi frequented was the Garden Hotel which is, today, Squatters Pub Brewery. Initially, Japanese Americans owned and operated this hotel, and in more recent times it was renamed the Boston Hotel. Izzi and his family brought their languages and rich cultural background to Salt Lake City’s west side. They, like many other immigrants, added to the city’s diverse population.

In our next installment of Salt Lake West Side Stories, we will explore Salt Lake City’s Chinese residents and how they establish gardens on the city’s west side.

Would you like to read the next post (Post 23)? Chinese Americans on Plum Alley and on the West Side

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Contributors: I thank public and oral historian Eileen Hallet Stone and Don Gale, both of whom contributed to the contents of this post.

This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

Juanita Brooks, The History of the Jews in Utah and Idaho (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1973).

Don Gale, Bags to Riches: The Story of I. J. Wagner (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007), ix-44.

Jack Goodman, “Jews in Zion,” in The Peoples of Utah, Helen Z. Papanikolas, ed., Utah State Historical Society, 1976, 187-220.

Rochelle Kaplan, “Utah’s Jewish History, The Earliest Utah Jews,” on Mormons and Jews, accessed April 6, 2023.

David R. Green, “1883: Salt Lake City Jews Dedicate a Shul of Their Own,” This Day in Jewish History, September 30, 2014, Haaretz.com.

Eileen Hallet Stone, A Homeland in the West, Utah Jews Remember (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2001), 3-20.

International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, Inc. 2014 Conference in Salt Lake City page

Leon L. Watters, The Pioneer Jews of Utah (New York: American Jewish Historical Society, 1952).

Miriam B. Murphy, “Reverend McLeod and the Building of Independence Hall,” History to Go (originally published in the History Blazer, March 1996).

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov